Vital Role of Infrastructure

Infrastructure is critically linked to economic growth and development. Well-developed infrastructure provides key economic services efficiently, improves the competitiveness, and extends vital support to the productive sectors. Over the years, basic infrastructure has been developed to an extent in India, but it is not sufficient, considering the country’s geographical and economic size, its population, and the pace of overall economic development. The huge investment required to develop adequate infrastructure cannot be met by the public sector alone due to fiscal constraints. The participation of the private sector in coordination with the public sector is required. Higher investment in good quality infrastructure is bound to result in increased employment opportunities, access to market and materials for the industries, and improved quality of life of the people.

Asset Monetisation and Infrastructure

Investment in infrastructure projects requires capital. Besides traditional sources of capital, innovative mechanisms have to be explored. Asset monetisation is a mechanism through which new sources of revenue for the government can be created. Commonly referred to as asset or capital recycling, asset monetisation is a widely used business practice, the world over. It involves a transfer of performing assets to the private sector for a specified period so that ‘idle’ capital is freed to be reinvested in other assets or projects for the delivery of improved or additional benefits. Asset monetisation is the key to value creation in infrastructure. It has been suggested as a tool to monetise operational assets at both the central and state levels.

Governments and public-sector organisations, which own and operate such assets and are primarily responsible for delivering infrastructure services, can adopt this mechanism to meet the ever-increasing needs of the population for improved quality of public assets and service.

According to NITI Aayog, asset monetisation needs to be viewed not merely as a funding mechanism but as an overall strategy for bringing about a paradigm shift in infrastructure operations, augmentation, and maintenance.

National Monetisation Pipeline: Structure and Components

In August 2021, the Union Minister of Finance and Corporate Affairs unveiled an ambitious National Monetisation Pipeline (NMP) that involves unlocking value in brownfield assets of central ministries and public sector entities “where investment has already been made, where there is a completed asset which is either languishing, not fully monetised or remaining underutilised”. This is sought to be done through asset monetisation mechanism involving private companies across infrastructure sectors.

(Brownfield assets refer to the projects that are already there in execution and need investment for further modification or operation as against greenfield investment which refers to investment in something that does not already exist but must be built up.)

The NMP is considered to be a medium-term roadmap for identifying the projects with the potential for monetisation across various infrastructure sectors.

With the NMP, the government aims to generate ₹ 6 lakh crore between FY 2021–22 and FY 2024–25. The funds will be used to build new infrastructure assets to help boost economic growth.

NITI Aayog developed the NMP, in consultation with ministries in the infrastructure sector. It has evolved from the mandate for ‘asset monetisation’ under the Union Budget 2021–22.

India’s National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP), detailing the infrastructure vision for the country, was released in December 2019. Its aim is to bridge existing infrastructure gaps and cater to its future potential. It envisages an infrastructure investment of ₹ 111 lakh crore over the five-year period (FY 2020–21—FY 2024–25). Financing of infrastructure investments on the scale envisaged under the NIP can only be made possible through a re-imagined approach, and a look beyond the traditional sources or models of financing. Accordingly, the NIP emphasised on innovative mechanisms, such as asset monetisation, for generating additional capital.

The NMP has been planned to be co-terminus with the remaining four-year period of the NIP. A sizeable inventory of infrastructure assets has been created in the country through public investment which can now be leveraged for tapping private sector investment and efficiencies. The NMP is designed to free up the value of investments in public sector infrastructure assets by making use of existent institutional and long-term capital.

The total indicative value of the NMP for core assets of central government has been estimated at ₹ 6 lakh crore over the 4-year period, FY 2021–22—FY 2024–25. The estimated value corresponds to about 5.4 per cent of the total infrastructure investment envisaged under the NIP and 14 per cent of the proposed outlay for the Centre ( ₹ 43 lakh crore).

It has been clearly stated that land and buildings are non-core assets and would not be included in the monetisation.

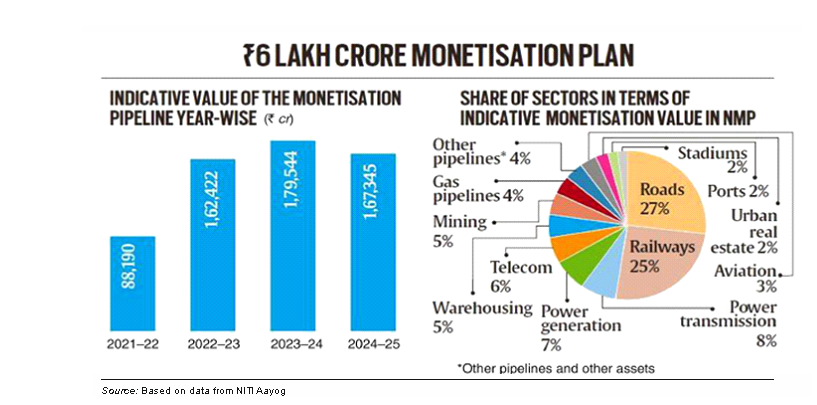

Sector-wise Breakup The breakup of the overall pipeline for FY 2021–22—FY 2024–25 with the sectoral shares is provided in the figure below:

The top five sectors by value under the government’s asset monetisation programme are roads (27 per cent), railways (25 per cent), power (15 per cent), oil and gas pipeline (8 per cent) and telecom (6 per cent).

More than half of the monetisation plan (more than 66 per cent) is from the roads and railways sector.

In terms of annual phasing by value, 15 per cent of assets with an indicative value of 88,190 crore is envisaged to be rolled out in the current financial year, i.e., FY 2021–22. The year-wise indicative value of the monetisation pipeline is given in the figure above.

There are over 20 asset classes across 12 infrastructure line ministries, which have been identified for the pipeline.

The assets listed for monetisation under the NMP include 26,700 km of roads, railway stations, train operations and tracks; 28,608 circuit kilometre worth of power transmission lines; 6 GW of hydroelectric and solar power assets; 2.86 lakh km of fibre assets; and 14,917 towers in the telecom sector; 8,154 km of natural gas pipelines; and 3,930 km of petroleum product pipelines. (The government has already monetised 1,400 km of national highways worth ₹ 17,000 crore, and five other assets have been monetised through a PowerGrid InvIT raising ₹ 7,700 crore.) Also open for monetisation will be 15 railway stations, 25 airports and the central government’s stake in existing airports and 160 coal mining projects, 31 projects in 9 major ports, 210 lakh MT of warehousing assets, 2 national stadiums, and 2 regional centres. The Centre also plans to monetise warehousing assets owned by public sector firms, Food Corporation of India and Central Warehousing Corporation, over the next four years for an estimated sum of 28,900 crore.

Working The money that the government will get for the transfer of the brownfield assets to the private sector will be in the form of either an upfront payment or a share in the revenue.

The monetisation of core assets under the NMP is expected to be carried out through public-private partnership models such as operate-maintain-transfer, toll-operate-transfer, etc., as well as structured financing vehicles such as Infrastructure Investment Trusts (InvITs) and Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). In a direct contractual instrument such as a public-private partnership, a private party would operate an asset for a specified period and earn revenues after it has made an upfront payment or allowed a revenue share to the government. If structures such as InvIT are used, assets are transferred to the InvIT which then sells units to public investors who make an upfront payment for a share.

Performance standards and key performance indicators (KPI) will be put in place, and real-time monitoring will be undertaken. There will be policy and regulatory interventions by the government, when required, so as to ensure that the process of asset monetisation moves forward efficiently and effectively. The steps taken will include streamlining of operational modalities, encouraging investor participation, and facilitating commercial efficiency.

States to be encouraged The NMP has been unveiled for the central units at present. In the spirit of cooperative federalism, states will also be encouraged to monetise their assets. There is a three-point scheme for that—if a state government fully divests its public sector enterprises with control, an equal amount of what it gets will be provided by the central government; if a state PSU has been listed, an amount equal to half the realised value will be provided; and in case of any other asset, 33 per cent of the value will be provided by the Centre.

Objectives of NMP

The strategic objective of the NMP is to unlock the value of investments in brownfield public sector assets by tapping institutional and long-term capital which can thereafter be leveraged for further public investments. The NMP aims to monetise the existing brownfield asset base in the country and use its proceeds for new infrastructure creation, recycling the future assets, and build a multiplier effect on growth.

The key objectives of the NMP are as follows:

- Serve as a medium-term roadmap for the line ministries and agencies

- Provide medium-term visibility to investors on infrastructure assets pipeline

- Provide a platform for ministries to track asset performance

- Bring in greater efficiency and transparency in public assets management

Developed in the backdrop of the unprecedented Covid-induced economic and fiscal setbacks, the NMP lists out assets and asset classes, under various ministries, which will be monetised over a period of time. It will provide a picture of the volume of assets to be monetised and the potential value that can be unlocked. It shall serve as a medium-term roadmap of the potential financing opportunities and drive the preparedness of public sponsors as well as private sector/institutional investors towards financing the infrastructure gap.

The end objective of this initiative is to enable ‘infrastructure creation through monetisation’ under which the public and private sector collaborate, each excelling in their core areas of competence, so as to deliver socio-economic growth and quality of life to the country’s citizens.

Critical Analysis

The NMP is a bold initiative. The Indian government has tried out asset monetisation at some level when the first Toll-Operate-Transfer transaction (TOT) of NHAI (National Highways Authority of India) was introduced. The NMP envisages a programme-based approach across multiple sectors. It is an ambitious endeavour, so doubts remain whether it can be successfully implemented.

Merits of NMP The NMP has many plus points as enumerated below:

- Monetisation is not the same as privatisation. As ownership rights are not affected, at the end of the lease, the assets would be returned to the government. The government remains the custodian of these assets. Moreover, sale of land is not envisaged. This takes care of the charges of ‘sale of family silver’ that the opposition often levels against the idea of outright privatisation of public assets. Monetisation can lead to improvement in PSU productivity by restructuring business units without changing the ownership.

- It can be a significant source of finance for much needed infrastructure development by recycling the investment in diverse operating assets, over four years.

- NMP reduces the burden on the government. It is very difficult for the government to operate all these core assets while working on building new infrastructures as well as maintaining day-to-day business and working for social welfare. With monetisation of assets, some of the government’s financial burden is taken care of.

- As the leased assets are operating, they will provide a regular cashflow stream, even as they do not have development and construction risk.

- After realisation of the proceeds from the NMP, when new infrastructure projects are undertaken, it will provide a much-needed boost to employment in the economy.

- Given that some assets will have a revenue growth trajectory (e.g., toll roads and airports) and some assets will have a fixed revenue profile (e.g., transmission assets), the pool of assets will have the ability to attract a diversified set of global investors.

- As the assets concerned are brownfield assets, they do not carry the risk of building execution; as such, private investment is likely to be encouraged.

- Buying a PSU in its entirety would be a capital-intensive affair. However, if segments of their assets can be leased, new entrepreneurs, who may not have a high net worth but want to make an effort in the infrastructure sector, would be able to afford to buy into this field. In the process, the NMP could encourage a new set of entrepreneurs in the infrastructure segment, avoiding the creation of monopolies.

- Cooperative federalism could be encouraged. To encourage states to pursue monetisation, the central government has already initiated the Scheme for Special Assistance to States for Capital Expenditure under the Aatma Nirbhar Bharat package in September 2020. Under the scheme, if a state government divests its stake in a state PSU, the Centre will provide a 100 per cent matching value of the divestment to the state, and, if a state lists a public sector undertaking in the stock markets, the Centre will give the state concerned 50 per cent of the amount raised through listing. With the NMP, if a state monetises an asset, it will receive 33 per cent of the amount raised from monetisation from the Centre, provided that the amount is used for capital expenditure by the state.

Concerns about the NMP

The top three sectors identified for asset monetisation include railways, airports, and coal mining. The main concerns raised around the move are discussed below:

- A very pertinent concern is that of monopolisation. For example, the telecom sector has a handful of market players. In case of an asset lease, who will lease or buy out the asset’s fibre network or telecom towers; it would either be one of the two players or a consortium of the two players. The same problem would present itself in the power sector where it is believed only a few players would remain. There is nothing in the NMP that would prevent the creation of monopolies and the problem of their control if they did emerge.

- A closely related concern is that crony capitalism may flourish as selected private corporations close to the political dispensation would get advantage. After all, there are only few industrial houses in India capable of working large infrastructure projects, and the same groups could participate across sectors.

- Critics have raised a concern regarding the aspect of depreciation of the leased asset. If a private sector company takes an asset on for a long period of time, there is nothing in the model to ensure that the asset you leave behind is nearly as good as the asset that was inherited.

- The threat of price rise for the end user is yet another concern. Unless there is an effective regulation, prices are bound to go up.

- There are apprehensions about job losses because the lessee, who is a private entity, is in control of operations and would control the employment terms, too.

- There are better alternatives to asset monetisation, according to analysts. Reviving investment demand can be achieved through debt monetisation which would have lower operating and transaction costs.

Suggestions for an effective NMP and Countering Objections

The government has to value the assets fairly and moderate its expectations from the NMP. Past experience with respect to collaboration between public and private sector suggests that valuations can make or break.

To take care of the problem of possible job losses, it may be necessary to opt for a lease under which the lessee takes the asset with the undertaking that jobs would be safeguarded. Though this condition could lower the lease rent or upfront payment, in the present times of increasing job losses and unemployment, employment safeguards are practically a must.

As for the fear of price rise, it has been pointed out that most operational infrastructure assets (power transmission lines, natural gas and petroleum pipelines, and airports) have a regulated tariff that is settled on the basis of cost-plus basis or through competitive bids at the time the service licence is obtained. The sector regulator or the administrative government department concerned would be setting the terms for any additional development or rehabilitation that a lessee would have done.

Many of the assets being monetised are in sectors where the states still have a dominant presence. The autonomy with which the sector’s regulator operates could either help licensees meet the objectives or create challenges on the policy and legal fronts. These aspects will have to be taken care of.

The NMP has to work out finer details, such as identifying revenue streams in various assets, creating a dispute resolution mechanism, and setting up independent sectoral regulators in those sectors that lack in this respect.

The government will retain oversight through the contract period, as ownership remains with it. However, undue government interference may be a hindrance to smooth functioning. The contract must be flexible enough to attract private investment.

The success of the plan would certainly enable funds to be recycled, which will be critical for the revival of the infrastructure investment in the country. But it will require meticulous planning, project packaging, and coordination. The government needs to get it right in the first few projects in every sector so that it can promote the idea and encourage investment.

The speed with which the fine print for the monetisation programme is finalised has a crucial role. As one analyst has pointed out, “Smooth implementation of the first ₹ 10, 000 crore will determine the fate of the ₹ 6 lakh crore asset monetisation plan. In essence, execution will be the key to fruitful realisation of the asset monetisation plan.”

Conclusion

If the NMP is to succeed, the contracts must be structured well. There are well-known examples of government-private sector collaboration, such as the PPPs of New Delhi and Mumbai airports under an operate, maintain and develop model; or the national highways model under the operate, maintain and transfer mode. There is little doubt that, if the NMP is executed well, it will prove to be a major reform in the infrastructure sector in recent times.

© Spectrum Books Pvt Ltd.